’White Man falling’ and other stories. On Aleksi Wildhagen

By Elisabeth Aarhus

-I paint and draw, or make works of art if you will, in two ways, combining both: straight from my gut and mind, and as a direct visual imprint of what was in front of me. Aleksi W.

Scrolling down my screen, through a vast number of image files with strange-sounding endings, my eyes graze documentations of Aleksi Wildhagen’s paintings. I reach to my left and pick up two of his books to flip through from the top of the pile stacked on my newly acquired cork-top desk. I relive my studio-visit and subsequent visit to his apartment in the middle of Oslo, his living-room painted in a flamingoish pink as the perfect backdrop for two of his powdered yellow paintings and a photo by Verena Winkelman. How difficult it is to separate the artist from his body of work in the particular case of Aleksi. Or him as an art writer for that matter.

As I research which pictures to use for my text I see a man, a boy even, a painter engaged in a full-fledged war with his canvas. There are thick, heavy-handed brushstrokes and a muted color palette; each canvas looks as if decisions are made before the mind has time to doubt itself, finding a way through the whole process in order to make the picture adhere to its inner logic. Typically, that would mean harmony and balance, a completion resting on certain given rules of composition and color but I find myself interested in the dissonance. I sense an artist fighting his own expectations about how the image is to come into being before him, something aggressive lingering in the same way a heavy bass might seem to reverberate in the room long after the music has stopped playing.

Brief Encounter.

I first met Aleksi Wildhagen at Olsønn&Barbieri’s seasonal party, just before Christmas about ten years ago. Olssøn it turns out, was Aleksi’s childhood neighbor and our mutual friend.

Or to be exact, I met him and his wife Ida Bringedal together. They were a team.

For some reason, the experience from this encounter stayed with me for a long time, like suddenly running into someone you’d been close to decades earlier and pass an evening with them as if you had met once a week that whole time. It left me elated, this chance meeting, and after having listened to them describing his then latest project at the Royal Park in Oslo we agreed to meet up in Skien the following week, a smallish city two hours from Oslo where they had just recently moved.

And just as quickly, like with that old friend you met late one night and swore to catch up with the following day, the plans you make simply never materialize.

Of course we became friends on facebook and kept each other up to date without much effort, for the sake of politeness, like little more than summer acquaintances. News meant to be shared on the public face wall. Nothing personal, really.

New Voices

And so it went, until early this year, when I came across one of the weekly reviews of art in Morgenbladet, penned by Aleksi Mannila. Neither my boyfriend nor I had heard of him before, but his pieces made me laugh. There was something familiar in his tone of voice, an openness and willingness to look for angles of understanding that might have been glossed over or left unexplored; a clear wish to communicate something, simply, even though he could be quite harsh on the artists themselves. I recall reading out loud, being amused at first, then slightly nervous on the writer’s behalf. There was no mistaking what he meant...

Socially engaged

Another half a year passed, along with it a few more honest, simple, daring and pulsating Friday criticisms, and I realized that Mannila was in fact the painter Aleksi Wildhagen whom I had once met years earlier. I looked him up on instagram, didn’t click follow straight away of course, but googled around his name. What had he really been up to since our encounter?

It really made all the sense in the world. Aleksi Mannila / Wildhagen was described as a socially engaged artist, testing out how he could use his expanded practice of painting and writing as a tool to engage with the world at large, and so, it took another six months until I got in touch and found myself across from him in his studio with a casserole of raw vegetables between us. Lunch was served.

Punk painter

Around us, the walls were covered with series of abstract painterly expressions, of attempts and finished works. Paintings, a few of which I had seen before in various exhibitions, and one’s I had never laid eyes on. I remember thinking to myself upon sitting down that on these walls, there was something truly free, someone willing to try anything for the sake of just seeing what happens, and it reminded me of a California punk band my boyfriend had mentioned years ago, called the minutemen. Their songs, because they often lasted only a minute and a half, allowed them the freedom to risk trying anything. Our band could be your life they sang in one of their songs, and it was an echo of this egalitarian spirit I found in the works of Aleksi Wildhagen.

Spontaneous Performativity

The critic Oda Bahr wrote about Aleksi’s work back in 2008 that he “combines traditional painterly techniques with an experimental and process-oriented method”. In his own words, Aleksi is quoted as saying that “I want to be present in the creation of my art much like a musician playing live – but where the live-musician is limited by duration, the painter is left with something tangible.”

This process, where spontaneous performativity meets the durability of the art-object in a painting, or a series of paintings, is typical of Aleksi’s work. Whether he is painting outdoors with his colleagues Patrik Entian and Jens Hamran in the group -& Co, standing in one of the allés of the Castle Park in Oslo dressed up in suit and tie, or making site-specific work at galleries and kunsthalles around the country, Aleksi’s work seeks to make not only paintings themselves, but the act of painting accessible and understandable, something that can bring artist and viewer together in the same room, on an equal plane. Through a basic realization that the one is lost without the other, Wildhagen’s work demystifies and toys with the stereotypes about artists with a capital A.

The investigative artist

Aleksi has used the term fieldwork to describe what he does, both on his own, and as part of the abovementioned -& Co, an artistic duo that only recently became a trio.

Painting is the common denominator for these three artists, and in the past years, the group has worked exclusively out of doors. Whereas Entian considers himself a realist, Wildhagen remains firmly entrenched within abstraction.

-I have an aversion towards working from photographs. I need to be able to make something mine. It is one of the things I value most about art, that it always contains this seed of freedom within it, says Wildhagen about this process.

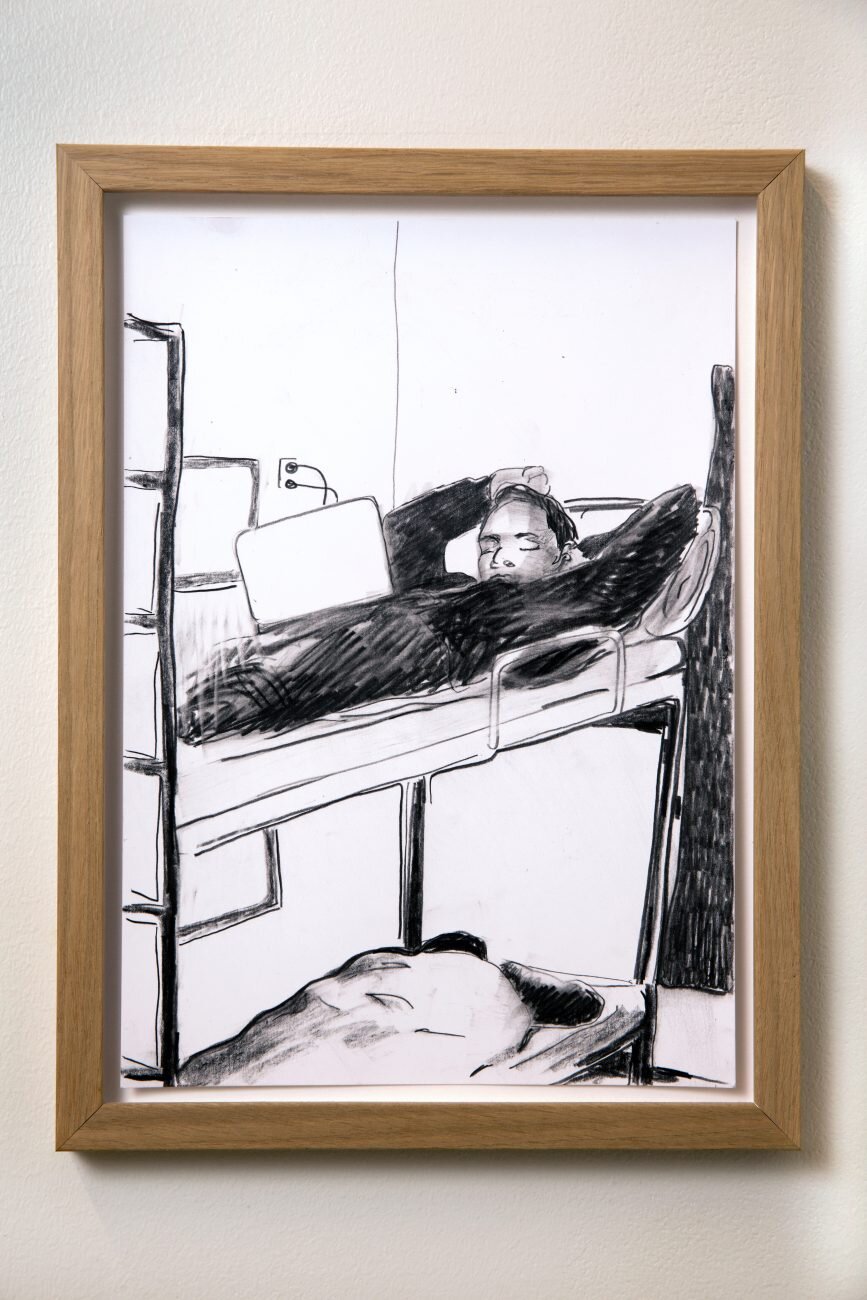

Working on this text I came across a project Aleksi had done for KORO (Kunst I Offentlig Rom), at the Norwegian military’s training camp at Setermoen. Stepping outside of the typical painterly role, opting instead for being more of an investigative artist, sociologist or documentarist, Aleksi’s aim was to look at the relationship between civilian and military life in this small community, and make drawings. He stayed in the barracks at Haslemoen, with the military personnel stationed there, making simple depictions of the life and goings on within the premises.

A move back into the studio

Whereas most all of the work Wildhagen has been doing for the last ten years has been made on-site or outdoors, his recent exhibition at Bærum Kunsthall marked a change, where field-work has been replaced in large part with a studio-practice.

Just last year, Aleksi moved back into his childhood home in Oslo. His father died when Wildhagen was only fifteen years old, and recently his mother passed away too, so after what I would take to be several shattering experiences at certain pivotal moments in life (on the brink of adulthood and approaching middle age), he is now the oldest in a new family constellation.

I take it that is part of what prompted him to move back to the studio after all these years, to take a moment to mix colors, to paint, read, write and stare out the window. I find myself asking whether he’s ok?

-I guess you simply have to trust that things will be alright.

And continues hastily.

-It’s about time really, isn’t it? Time itself becomes much more tangible when you have children. It used to be something abstract, whereas now the narrative lineage becomes very real. It’s absurd really, this paradox. The time we’re allotted is obviously very short right, and yet, life is long, feels long. These are the inherent contradictions I keep nudging up against, keep attempting to free myself and my work from.

But criticism, how did that fit into this plan?

-It’s not something I planned on doing, like all things, a set of events took place and swiftly, even by coincidence (and a pushy wife) I found myself writing about exhibitions. I think it’s fairly obvious that I take a great interest in the extended field of contemporary art, and I have for a while been thinking about how I could contribute, not just as a painter, but with other means. It occurred to me that writing about art not only allowed me to engage with other artistic practices, it offered me the chance to take part in a large conversation, on a societal level, about what art can contribute, and in which way. Ideally I’d like to open up the scene so that some of those who might feel intimidated or for various reasons uncertain about how to approach art today, can come inside rather than just walk on by. The art-world exists in the real world, and there is no reason why the two should be separated. Perhaps this is why art is sometimes scoffed at by those who don’t have a stake in it- it seems terribly preoccupied with itself and its own concerns. I’d like to open up the space so that the mutual benefits can become apparent.

An open door to the Contemporary Art-world

When I hear Aleksi speak about opening a door between worlds, it occurs to me that he might as well be talking about his own artistic practice, that writing and painting for him are in fact two sides of the same coin, a currency aimed at making an audience participate, or at the very least engaging them in a fairly direct manner. Whether through small newspaper columns or by rigging up his easel and donning a suit, Aleksi is bent on delineating our shared reality in such a way that it allows us to take part in each others lives. As simple as that.

-Well, it definitely looks like a cliché when I dress up as a “painter”, or a different character, but I am really invested when I do this. Performativity is about taking things seriously and see the beauty in what exists, wherever one happens to find oneself, he says. I think that my investment in it becomes visible, in turn making sense to the onlookers, allowing them to take part. A new space emerges in this process – it’s as if we all become present in whatever is being painted.

A better painter

Going outside to paint the natural landscape has been a painterly exercise for centuries, and for Aleksi it still holds a vital experience.

-To stand outside for all these years, painting and engaging with the goings on around me, whether it be untouched nature, the side of a busy highway or the front yard of someone’s house, has not only made me a better painter, but literally more awake. Just by being in the world, taking care to notice the things around me, it’s as if meaning and purpose hits me like a slap in the face wherever I look. And yet, over the years I’ve noticed that I’m less interested in the subject matter than I am in the painting as a site in and of itself, a space that exists in tandem with my own mind. The subject matter is simply there as a motivation, and this is why I have looked to the periphery, to these non-places, because in the end the subject matter can be anything as long as the painter is motivated and able to give the image a certain weight. So the move to the studio is in fact not as big a change as I had perhaps thought. It’s a challenge, but it’s still up me to create this meaning and construct a sense of purpose instead of locating it outside of myself.

Immediacy

I look down at the smooth undifferentiated surface of my telephone, then glance up at the mess of swirls on canvases hung on the wall, my eye grazes the splotches of paint covering the floors all around me in his studio and think to myself that perhaps Aleksi’s work is a kind of antidote or space for mindfulness, to use a word I very rarely take in my mouth without smirking. We are at a moment in time where many of us, without thinking about it, spend lives in a virtual world, and we need the experience of smelling the paint, feeling its raised contours with our eyes, seeing ourselves as bodies in space, where are our actions and thoughts have very real consequences. There is an immediacy and lack of mediation to the works of Aleksi Wildhagen, a wish to show not simply the staid result of a certain period of work, but the work itself, with all its successes and failures. At times he tells me, he has even hung paintings on the wall without letting them have time to dry first, the fresh smell of paint invading even our sense of smell.

Here and now

Moving indoors was not just a practical matter for Aleksi. Even though years of painting outside took its toll on him, like many artists, Aleksi kept noticing a nagging question in the back of his mind; what, if anything, holds importance?

-Navigating the artworld may sometimes get in the way of creating and showing the work we actually want. Sometimes, as with so many other occupations, we simply lose our way; we enter the middle of our lives, we have children, our parents perhaps die or at any rate get old, we’ve been at the same job for a decade perhaps, so I guess I have noticed that I have this need to ask myself, every day, what is important, today, here, now.

A couple of years ago, Aleksi and some of his painting colleagues had set the ground for a large-scale project, a performance of sorts where they were to sail across the Atlantic, painting all the way, and ending up in New York City where they, on the basis of the idea itself, had been accepted as members of the prestigious Explorers Club in Manhattan.

Even though everything was set, the mission funded and the membership secured, the project as a whole never materialized. Instead, Aleksi went tramping about Eastern Europe, painting and drawing and living a kind of nomadic existence.

-Today, looking back on it, a part of me is glad the crossing didn’t happen at all. Perhaps we got slightly caught up in how far we could take these projects of ours. The idea was good enough, but in hindsight, the scale of it was maybe too large for it to be relevant on a smaller level, he says.

Which is exactly where Aleksi wants to be at the moment.

-I’ve come around to the fact that I don’t have the need to go anywhere at the moment in order to explore.

-You know what? These carrots, right here in front of us for example, the one’s you’ve been chewing on - there are indefinite ways of representing them, in words, or with paint, to name just two. If you’re good at it that is. The challenge is still here, now, to feel that I’m good enough at it, at painting, at depicting what I see… I’ve taken up again windsurfing for much the same reason; it’s a challenge, something I’m learning, something I’m testing out, something I’d like to be able to do, not in the sense of conquering it, but of being out there doing something, gaining experience, nudging up against a sense of freedom…

Essential to be critical

In addition to his ongoing arguments with himself in the studio, and his writings in Morgenbladet, Wildhagen also works as a teacher or instructor, doing workshops with youths.

-Interestingly they want rules, boundaries. They instantly reflect and comment upon what they do, but as soon as you tell them to just do it, they clam up, become paralyzed. Large formats terrify them, so I give them small sheets of paper, and just two colors, red and sepia. They have a great need for instructions, outlines, so I tend to start out by telling them the genesis of drawing. I give them my own private why of drawing, rather than how.

The most difficult thing is to set the kids free – they’re simply not used to it, they are terrified of doing something wrong, of making mistakes.

-I’ve thought about how this applies to my writing. I think it essential to be critical, to ask questions about given rules and predetermined ways of doing and seeing. There is no truth in the sense that there is no final answer to the questions art deal with. So, when I write, I have to allow myself to say something wrong, or to risk taking a stance that might later prove to be wrong, or not nuanced enough right?

So have you ever been wrong in any of the pieces you’ve written in Morgenbladet?

-Well of course there’s a difference between being a child learning to use drawing as expression, allowing oneself to fail, and that of taking on the role of a public critic, saying something within the confines of journalism. I have to be conscious of the fact that I can be wrong, and should be able to say it. That being said, the things I’ve written obviously still exist out there, but there are certain things I’ve thought, in hindsight that I criticized rashly and could have done differently given more time, absolutely.

White Man Falling (Flesh Tint Etc.)

Which brings me to the press release for his latest exhibition White Man Falling (Flesh Tint Etc.), at Bærum Kunsthall. If there is one criticism I hear again and again from gallery-visitors, it is that the relation between the works on display and the press release is often far-fetched. In this exhibition, there was immediately a one-to-one relation between the two, a very explicit text telling us what the pictures are about. How would you rate that, as a critic?

-Once I had written it, it felt right. At that moment it spoke to the feelings I had about what was going on around me, it was borne of necessity really. But, as soon as I sent it out, I had my regrets. For those who didn’t have the chance to see the exhibition, it explored masculinity and structural racism today, and it did so in a very direct manner by making use of a, or even the standard oil paint hue called Flesh tint. Aleksi called the show White Man Falling (Flesh Tint Etc.) One of the large canvases featured a body free-floating in space, others made explicit use of the body and all of them were painted in broad strokes with the generic oil color Flesh Tint.

-Well, I am slowly learning how to deal with being wrong, in my writing and in the studio, and when I followed that line of thinking leading up to the exhibition, I realized we were living in a moment where I, by virtue of being a Caucasian male, stand for and am looked at as inherently vile, or wrong. Even though the white straight male to some extent still runs things, and even though patriarchy is still a dominant factor, the hegemony of the white man is to a certain extent over. I am no apologist for the structural inequality, racism and misogyny propagated by those who have looked like me, but I do find it interesting to take into account, particularly when you look outside the typically elitist circles of the art world, finance or what have you, which kinds of realities that man is confronted with every day. I have to ask how I relate to that?

Fundamentally about Freedom

I look over at one of the smaller paintings on the wall, to what looks like a tornado, ravishing its surroundings and making the painting a large whorl of something indefinable. My boyfriend suggested Munch when seeing them.

-I seldom refer to other artists in my work, or particular paintings – to me, it is fundamentally about freedom, about what it means to be free. How are we to lift the constraints that restrict us every day, those we are aware of as well as those that simply lay there, structurally. Which is why I chose to use such a bold and generic color in the white man falling project, to show that even our palette is limited by a very narrow conception of what the color of flesh is.

-And now, looking at it, I wonder if we haven’t gotten further in our minds, than we in fact have in the real world. In the west for example, new zones of conflicts are dawning. The apocalypse brought on by climate change for example, or the migrant crisis. I am really unsure about how healthy it is to hammer down these realities of a looming disaster to young children for example. I mean, if the narrative becomes too destructive and dismal, I’d think we’re bound to resign ourselves to the end of days and end up not giving a damn.

Return to the park

It makes me think again of the trees in the castle park, where our conversation started all those years ago, what that was in fact all about. It was something he had heard on the radio, a brief notice that 180 trees lining the alleys surrounding the Royal Palace in Oslo were to be cut down. They were lethal it was said, in such bad shape that they had to be cut down so as not to hurt someone.

To Aleksi it had sounded absurd.

-Apparently, only 15 trees had been said to be in need of care, so rather than deal with just those, all the trees in the park were to be torn down in one go, just be done with it you know? Everyone was quiet about it. The head gardener, the king and queen.

-Aleksi had no intention of becoming a sort of treehugger, but there was something about this process that resonated on a larger scale, a tendency of sorts.

And so he donned a suit, played the part of a painter from a bygone era and set up his easel under the beautiful elm trees and started painting.

Aleksi had just moved to Skien at the time and had to set himself some rules. So, in his quietly humorous way, he limited himself to painting two to five hours every morning, which was exactly how long he could have his car parked outside the park. For a period of a few weeks, at 3:30 he got up and arrived before 6 in the morning.

His idea was that the paintings be given to the royal palace, a gift with an obligation embedded.

There were thirteen paintings in all, and on of them was exhibited across the park at Kunstnernes Hus. The piece, titled Til det Norske Kongehuset (To the Norwegian Royal Family) received a prize during that years Fall Exhibition and the series of thirteen paintings was exhibited at Trafo Kunsthall in Asker (Thirteen Exposures). To follow up Aleksi donated the piece from the Fall Exhibition to the Royal Family together with a publication he made about the project, and to this day, all the trees are still standing.

Was it because of the paintings, I ask, does art really matter?

-Sure, art matters. Art is important, but not much more important than other things that are important he says with his usual wry smile. The paintings are what they are. I stand behind them, he says softly, before picking up the last carrot from the casserole between us.

I’ve been in the studio for three hours, perhaps four. Aleksi hands me a book to take home. I flip through it the following day. The book is called El Rancho and consists of photographs taken of Aleksi and Patrik while they were working on location, at Berith Andrea, Terje and Aiko’s Borgen Ranch in the small town of Hvittingfoss. In it, photographs documenting the act of painting as if it were a performance are set next to pictures of household nick-knacks, of the trailer the artists sleep and rest in, and various curious photographs of the hosts themselves. This extended frame seems to be a testament to how painting is not simply painting for Aleksi, but a lifestyle, a way of engaging with the world. Painting is not something your produce simply to have and put on a wall to be looked at, but something expansive that reaches beyond itself to forge connections and in the end have the potential to really impact the lives you and I lead.

WHO: Aleksi Wildhagen

Born 1976 Helsinki, Finland

Visual Artist MFA, painter, educated at National Academy of fine Arts in Trondheim.

Freelance art critic Morgenbladet, lives in Oslo with Ida Bringedal and their two children.