Leversby - just because

REJECTIONS

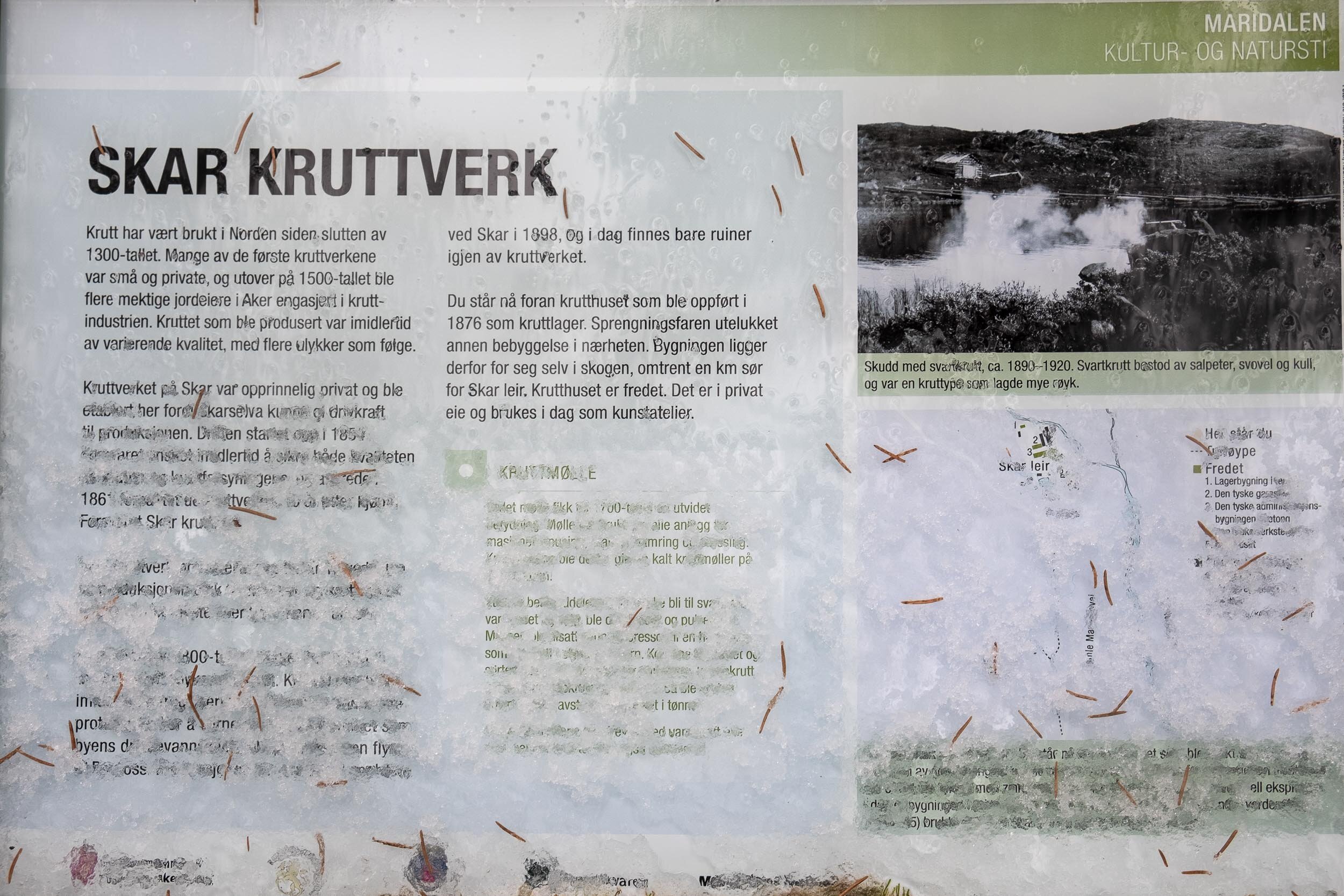

A few weeks back, Rolf, an older friend of mine got in touch, asking if I was aware of an exhibition space called Krutthuset, located half an hour outside of Oslo, in the middle of the woods. There was a show on, he explained, by the Norwegian painter Dag Leversby, and he would like to see it. -Would I? Though I’d travelled out there numerous times in my mind, and on Instagram, I had yet to visit the space in person, and at some point a few years back I actually approached one of the owners, artist Vera Wyller at an opening og a show at Galleri Riis, asking her if she’d let me come photograph it. At that point, she and her husband Sverre had not been based in Oslo for several years, having spent time living in Berlin, but the couple seemed less than enthused at the idea of someone coming in to photograph what today is their home, their studios and sometimes, an exhibition space. The structure now dubbed Krutthuset (it was formerly a depot for gunpowder and hence the location) was essentially an old ruin when the couple bought it from the military almost a decade ago, but in the span of a few years, they completely overhauled the space, rendering what was for many years a passive and empty storage facility, into something altogether more vital.

words & photos: Elisabeth aarhus

warm welcome

As it turned out, the exhibition my friend had asked to go see had closed just the day before, and with the polite rejection years earlier lingering in my mind, I’ll admit I was slightly apprehensive about reaching out to Vera – but – having thought the better of it, that this time around it wasn’t my curiosity that took the front seat, but my friends interest in the show by Dag Leversby, I thought “f- it” – and sent Vera a gentle request. And just like that, a friendly message from her about how they’d decided to keep the paintings around just a little longer even though they’d usurped both his and her studios – and of course, we were more than welcome to come see them before they’d be taken down.

Almost lost

We took off that Tuesday morning without having plotted in the coordinates, under the assumption that the structure we’d seen photographed a number of times would reveal itself to us so long as we followed the main road to its logical conclusion. As we entered the cul-de-sac by the now decrepit military compound in Maridalen we knew to be in the vicinity of Krutthuset, we had clearly overestimated the latter’s visibility.

We called up Espen on the speaker phone, Morten (Andenæs) our designated driver for the day and Sverre’s gallerist who, always in the know -told us to’ back up, make a right, follow the main road until you see a mailbox on the right hand side, then make a three point turn up what appeared to be little more than a muddy side of a hill’.

The backseat drivers doubted the whole project.

Really, here?

A place for us

The first snow came that day. Not the pristine, white kind that silences footsteps and figures in many a poem, but the heavy october slush that mixes with the dirt of the trail, making it all too obvious that we had not prepared our car for this sort of an outing.

Morten backs up the trail so that in case we get no further, we can simply roll down again. The car slides around corners, stacks of lumber appears on all sides; this is clearly not a place for us, on a day like today. He gives up. The driver that is. Parks under a large pine and orders us to get out and walk the rest of the way, with no idea whatsoever of the distance we’ll have to trek.

We’re obviously not dressed for the occasion either. The heavy, wet snow melts as it lands on us. On our way up the muddy hill, my leather boots draw their last breath, falling apart at the welt, with Rolf – who in his heyday ran KAMIKAZE, the clothing store in Oslo for years, where certain discerning artists (I won’t reveal which one’s) would come in and trade works of art for a variety of fashion items, trotted on unperturbed in his low cut, sleek sneakers.

A strange calm

Anyway, schoos schmoos I think to myself (with very wet socks) as we round a bend, and there, in the clearing, an overwhelming brick structure appears on top of a hill. Its earthy, I’d even say fleshy hue a beacon amid the wet black trees and the grey-brown snow on the ground. We make our way along the façade of the building, entering around the back through tall glass doors. It’s warm inside, hushed. Clean, functional, and I’ll say it again, warm. The wooden stove is lit, alive and burning. In the first room (which also functions as Vera’s studio on other days) the long table is set with 4 Wedgewood cups and plates-possibly placed there for us? in front of the fire. The ceilings are tall and some of Leversby’s paintings are leaning up against the walls in stacks, while some hang on the walls.

There’s something sacred about the space opening up to us– not necessarily in the transcendent sense – as if it invites and incites those stepping inside to reflect on the importance of work. A strange calm overtakes me as I look around. Everything seems to be in its right place here. Even Leversby’s series clumsy /stringency inhabits the space with a certain matter-of-factness, its title DERFOR (or because) entirely apt given that it is an answer which in and of itself renders questioning moot.

DERFOR is comprised of 80 works of art. Two thirds are hung neatly in two rows in the large studio-cum-exhbition space, and the remaining one third are stacked along the walls of Vera’s studio where we entered. In a spirit of generosity, we are invited to handle the works themselves, to move them around, the feel of linen against the tips of our sanitized fingers is rough.

For the occasion, Sverre and Vera’s tools and works in progress were neatly stowed away, concealed within invisible rooms, behind walls and up under the ceiling. By handing over the stage like this, we’re given an overwhelming peek into Leversby’s immense output. The sheer volume is testament to an artist who seems obsessive about work, a painter unable to put his brush down.

When they had first spoken about doing an exhibition, Vera had asked him head on, the all important question, of why. Why keep painting, at this pace, especially when he’d been reluctant for years, to show much of it.

I’ll paint so long as I have something to say he’d replied swiftly.

- To whom, Vera parried?

- To painting.

For those of us who follow him on Instagram, we could make the case that it is not necessarily only the paintings themselves that he’s communicating with, but a general audience out there, and in the course of his career, he has developed a following. Leversby is most known for his project Magnolia Cross, a comprehensive body of work that unfolded over the course of nearly two decades. The paintings were precise, meticulous and finely tuned into a certain register, and then - last year he showed an exhibition at LNM (Landsforeningen Norske Malere) that made a clean break with this asceticism.

Under the moniker Clumsy / Stringency, the new paintings were described as being “cut from a different cloth altogether; with a restless immediacy, energy and a certain nerve, they are vital, powerful. There is a certain roughness to the process, the brushstrokes applied without hesitation, the traces of the paintings coming into being were visible.”

Manic Output

At a glance the somewhat manic output, pressed together so as to cover the walls of the exhibition space at Krutthuset in two neat rows, hung side by side, shoulders nudging, expresses an urgency. The often improvised and unruly energy is erratic, frustrating and challenging and yet, despite the lack of clean harmony so visible in his earlier works, these paintings on display feel, for lack of a better word, right. As they should be. It’s as if all the energy that was kept at bay and harnessed during the Magnolia Cross years had suddenly, forcefully, been set free and there was no way to hold it back. A storage space for explosives indeed.

But also-upon entering the second big space in the building, where Sverre usually works- I stop and smile. Little did I know that these paintings would reach out and leave me overcome with a sudden moment of deeply felt happiness. The generosity of it all. An artist and his facilitators, in this case Krutthuset.

A catalogue of works

A beautiful catalogue accompanies the exhibition, made on sight with the same aesthetic sensibility that runs through the entire Krutthuset project, and in it, Vera writes that perhaps these paintings are a result of Leversby reaching a point in his life and career where he simply stopped giving a damn. It’s not uncommon for artists (or anyone really) to reach a point where they realize that they had run on autopilot for so long, trying to adhere to certain self-imposed rules and regulations about what kind of work one can and should produce, that as another artist I know said it so well – we become more preoccupied with not missing, than in taking pleasure in simply doing the work because it allows us to express something hitherto inexpressible. Be it applying paint to canvas, chiseling away at a stone, aiming a rifle at a target or putting words to paper, what these things do is to allow us a certain vitality, but too often it gets mixed up with the machinery of consumption, of posture. If I understand Vera, giving a damn meant being part of the machinery, and Leversby’s not giving a damn meant perhaps that he allowed himself the freedom to do what he pleases.

I’ve often had a difficult time getting past abstraction, often feeling as though the hermeneutics of the painted space has little relevance to life as such, and yet standing there face to face with this work, what tickles me the most, beyond the calm chaos, is the excess of life. I think of Freud’s death drive, of that particular, manic drive to live, more, precisely because we know that we will die; a desperate affirmation of life in the face of anxiety and death and it is this I sense most urgently with Leversby’s clumsy stringency. At the end of the catalogue, the artist writes how the spaces he creates are battlegrounds for an array of voices - Iron-Harry, The Inquisitor, The good Doctor and Lovely Rita among them - most of which we take to exist within Leversby. Sometimes they are in harmony with one another, sometimes at odds, but looking to the paintings on display, they are continually engaged in egging each other on to keep going, to paint, paint, paint. And in the end, as I read these words of his while drinking the above mentioned cup of coffee from beautifully cut porcelain, it is the one he calls “The Boy”, who in his own words “is trying in his own way to liberate his Libido - to create a place of his own” who most clearly stands out.

On instagram:

Krutthuset @__k_o_s_a

Leversby @dagleversby

NOTE

The activities at Krutthuset are run by Samvirket Krutthuset Oslo SA - K.O.S A. Vera & Sverre Wyller and Sara R.Yazdani.

The latest addition to the project, is an outdoor exhibition space with its own program. Jane is a diorama which can be experienced both night and day as it is illuminated and has a large glass facade. Jane is designed by Vera, as much a sculpture as it is an exhibition space; a pavilion on the edge of a small lake in the woods. It was built in order to exist as everything else does in the woods, as nature, and yet, by showing work that defies the simple dichotomy of humans as either occupants or completely indistinct from nature, Jane is a foray into how art can articulate existence in novel ways.

Also Pictured in this article, is the exhibition The Heart does not Beat in the Middle of the Body, by Endre Opheim. On view in the Jane pavilion.